Press a button to evaporate potable water

Here are some expanded notes on one of the most marvellous things I’ve been involved with. I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who helped to make this happen. I didn’t do it by myself, it’s an example of good people and the right conditions. You can also read our official and approved blog post.

In April 2025 the Government Design Principles were updated with the first new principle since they were published.

This was with number 11: Minimise environmental impact.

Here is the whole principle:

11. Minimise environmental impact

We need a large amount of energy, water and materials from the real world to build and run digital services. Even a small improvement to a service will help reduce its environmental impact, including climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. Follow sustainability best practice to reduce the environmental impact of your service across its lifespan.

There’s a lot in here:

- The fact that digital services have an impact on the real world, and require a large amount of energy, water and materials.

- That small changes, embedded within a design system, can be cumulative – small improvements are multiplied. These small changes reduce the environmental impact of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

- Sustainability best practice should be followed. This is a deliberate variable to keep this design principle relevant as best practice changes over time.

Each design principle has a space for blog posts which help to illuminate the principle. This also helps the principle to stay fresh and relevant.

The beginnings

Web sustainability was emerging as a concern, but it wasn’t well known. We weren’t talking about sustainability in the design team at GDS. Pages on GOV.UK had always been light (accessibility and sustainability go hand in hand), but since 2022, AI and video were increasingly being mentioned by senior management.

I read Tom Greenwood’s excellent book ‘Sustainable Web Design’. The W3C published the sustainable web guidelines. The NHS had recently added sustainability to their design principles. A lot of progress was happening outside of GDS.

The intention behind setting up a group was to create a platform to explore digital sustainability, and bring it into the design team’s awareness, consideration and conversations. In 2023, I created a Slack channel called ‘Planet centred design’1 and invited designers at GDS to join.

At that time in GDS we had community objectives (in our line management for designers). These are permission slips to spend time doing things which nurtured the design community, such as a group focused on exploring sustainability.

It is quite easy to get people to join a Slack channel. It is less easy to get people to show up to meetings.

(But enough people did!)

Press a button to evaporate potable water

There was, and still is, a general lack of understanding that digital things have a real world impact.

People are increasingly aware that using tools like ChatGPT involves evaporating enormous amounts of potable water. This is because data centres are hot and require water for cooling.

The government design principles didn’t cover environmental impact of government services. So we focused specifically on the need for a new design principle.

The government design principles

The government design principles have been around since 2012. They have been hugely influential.

They’re easy to remember and apply: for example, “Start with user needs” is the first design principle. They are the heart of more detailed guidance.

According to Tim Paul, they were written in about two weeks by a handful of designers. There were no committees or workshops.

The GDS design principles were renamed to the government design principles about a year after they were published. This meant their scope was now much larger – they affected more people.

When updating them in 2025, we had a responsibility to make sure a range of people and disciplines were represented in the discussion. We also wanted an opportunity to address any concerns or questions that might arise.

Getting people involved

We kept the collaboration process lightweight:

- We recruited 12 people from different disciplines and organisations.

- We ran two workshops only, each an hour long.

The working group contained representative of each discipline. That included content, developers, research, interaction design and service design. We included representatives from teams focusing on Artificial Intelligence, design systems, and organisations including DEFRA, DWP and HMRC.

I was initially worried that involving a group wouldn’t result in something better. I am now absolutely certain that thanks to involving multiple people in this process, and going through the workshops, we ended up with something better. We had consensus, and we had evidence of consensus. We also had a group of people in different teams and departments who now had a stake in this work, and knew about what we were doing, and would be able to share it with their teams and departments.

Workshop 1: what’s a principle good for anyway?

The first workshop2 focused on the purpose of a design principle. How were they used? What was their utility? What worked well, what didn’t?

We asked users about sustainability, and what we should be covering. We identified and roughly prioritised things that we needed to include.

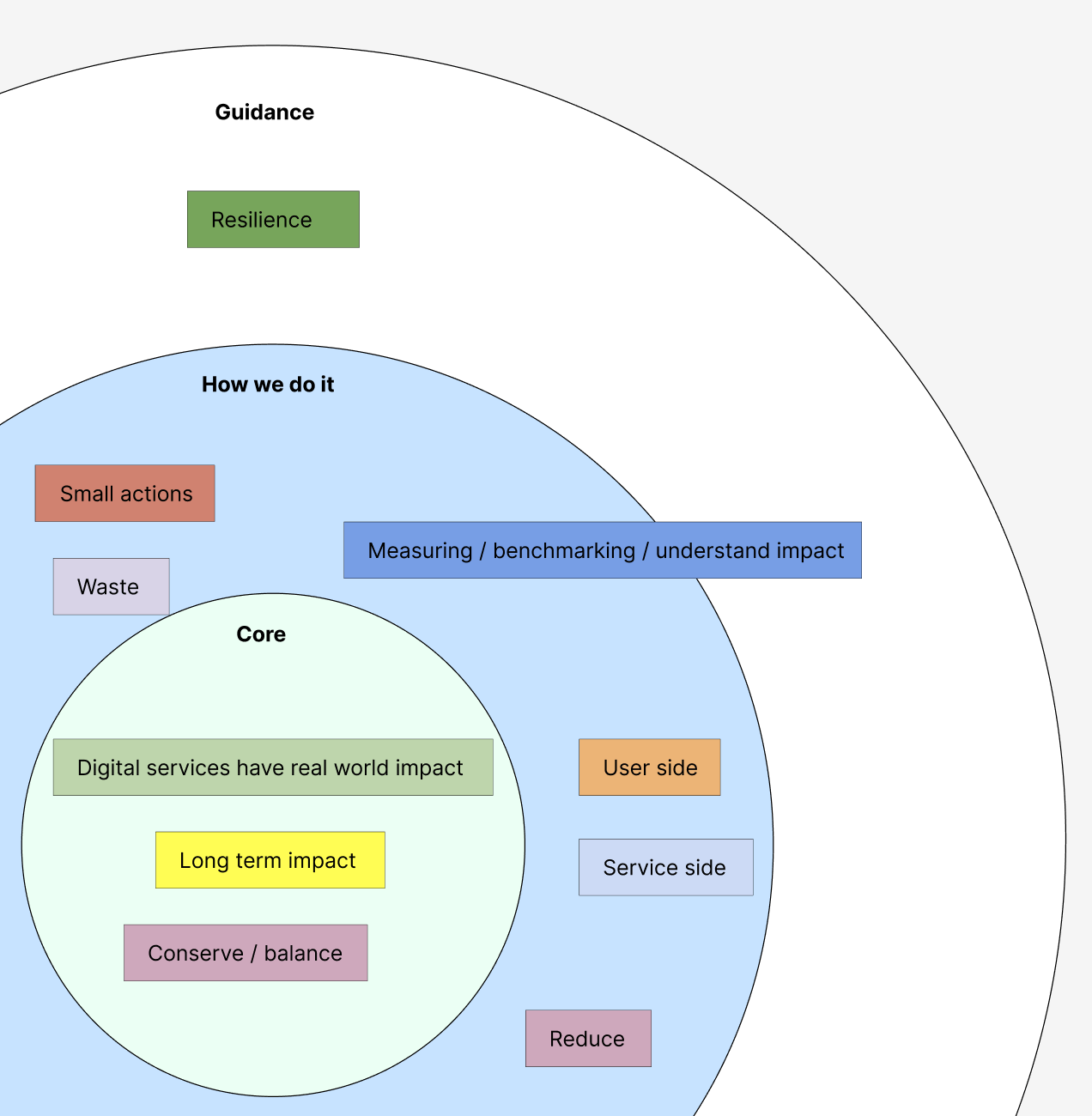

Here’s a snapshot of our analysis, above — the image shows three rings, with core / primary themes at the centre, how we do it as the secondary ring, and the tertiary ring showing guidance.

We grouped themes emerging from the workshop. We prioritised things by the frequency in which they came up. At the core we have “digital services have real world impact”, “long term impact”, and “balance”.

There are more themes on the outer rings that need to be supported with guidance.

We couldn’t fit everything into the design principle, but we wanted to make sure we captured the spirit of everything that emerged.

We took our draft into the second workshop for feedback and editing.

Workshop two: editing

The second workshop focused on critiquing, editing and rewriting this draft.

Iterating, sharing, emerging

Once the workshops were done, we iterated multiple times. Then we iterated again. Then shared it with the working group. Every word needed to earn its place.

We might have been stopped

Throughout this process, we did everything we could to reduce the risk of failure. We were in touch with senior stakeholders in different programmes at GDS. All senior stakeholders we approached to sponsor our Service Manual change request agreed to it. We had evidence of cross-government engagement and consensus, and precedent set by other departments taking action for sustainability.

While this all helped, we couldn’t control every variable, especially since GDS was being moved into DSIT at the time. The ultimate risk was that we did all this work for nothing, and we’d be stopped by senior management, or DSIT — who needed to approve the blog post.

Fortunately none of this happened and we sailed through.

Other obstacles we had to overcome:

- We had to find out who owned the 10+ year old government design principles page. It wasn’t technically owned by any team. It made sense for the Service Manual to adopt this page, and we were relieved they were happy to do that.

- Getting people to show up to the workshop. Getting people to reply to our emails. Coordinating editing with the working group. Given we were doing this around our day job, it wasn’t always easy or straightforward.

- Finding the right words was hard. The workshops really helped with this, as we knew what themes we needed to prioritise. Despite unfounded fears we were forming a design by committee, the workshops were extremely helpful and valuable. It helped that we kept the number of attendees low, and we were very selective about who we invited. We were blessed to have some really excellent participants.

Receipts ready for Service Manual change request

We had all of our receipts and evidence ready for our Service Manual change request. We had evidence of consensus, having engaged people via a collaborative process. We also had the precedent set by other departments.

Progress made by one department or organisation always helps everyone.

The open contribution model makes good things possible

What made this work possible is that GDS has an open contribution model in the form of the Design System and the Service Manual. Thanks to this, we could submit a change request.

It’s important to note that this work happened ‘bottom-up’ from the design community (not a top-down objective from senior management).

Where open contribution models exist, individual contributors can make important work happen.

Three cheers for the amazing Service Manual.

Thanks to Cennydd for reading the draft and suggesting some good edits.

-

With Ned Gartside’s blessing, I forked the name ‘Planet-centred design’ from Defra’s cross-government group. ↩

-

Another barrier was tools that can be used by people across government. We used Padlet, which despite our best efforts, still had some problems. The best tool for cross-gov collaboration remains an unsolved problem. ↩